A Hymn of Release: Transcendence in the Face of Mortality

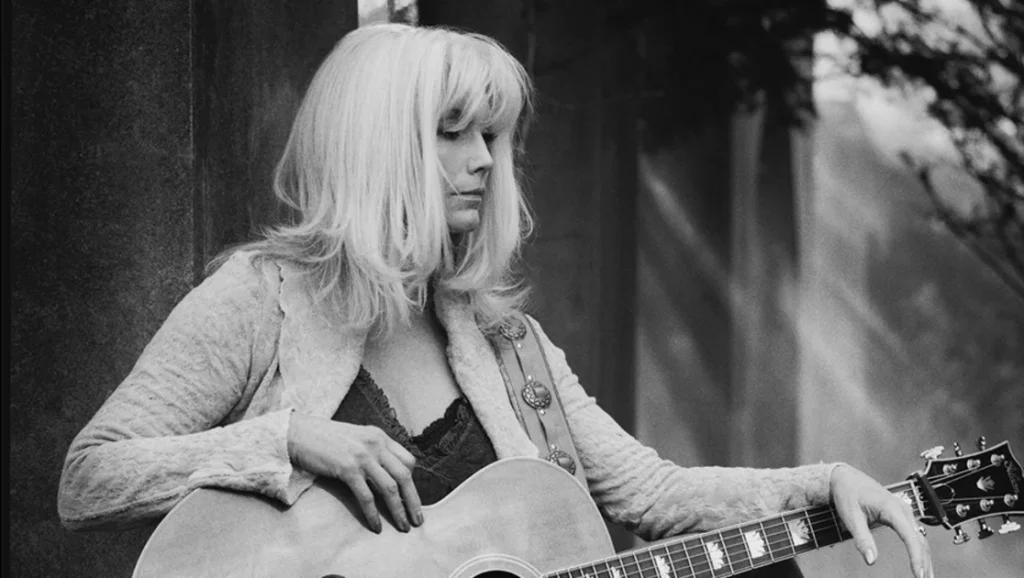

When Emmylou Harris released “All My Tears” on her 1995 album Wrecking Ball, she stepped boldly into new sonic territory—a luminous blend of country roots, ambient textures, and spiritual introspection that redefined her artistry. Though the song itself was written by Julie Miller and first recorded by Miller and her husband Buddy Miller in 1993, Harris’s rendition became one of the emotional pillars of Wrecking Ball, a record that reached No. 94 on the Billboard 200 and earned critical acclaim for its ethereal production under Daniel Lanois. Within that body of work—hailed as a turning point in Americana—“All My Tears” stands out as a prayer rendered in sound: intimate, fearless, and radiant with hope beyond sorrow.

The origins of “All My Tears” lie in a personal reckoning with mortality. Julie Miller composed it after the death of fellow musician Mark Heard, infusing the piece with a tender acceptance of death not as an ending but as a passage into freedom. When Emmylou Harris took the song into her own voice two years later, she transformed it into something almost sacramental. Her delivery is not mournful—it is serene, imbued with the quiet wisdom of someone who has seen grief transfigured by faith. Harris’s timbre, fragile yet unyielding, floats above Lanois’s spectral guitar tones and subtle percussion like a soul unmoored from flesh, ascending toward light. The production wraps her in vast spaces—echoes that feel less like reverb and more like eternity itself responding to her voice.

At its core, “All My Tears” is not a lament but an emancipation hymn. The lyrics—rich with biblical imagery and spiritual symbolism—turn death into renewal: the shedding of worldly burdens for divine liberation. There is no fear here, only release; no darkness, only illumination. In Harris’s hands, these themes transcend religious boundaries to touch something universal—the human longing to believe that love outlasts decay. Her phrasing emphasizes gentleness over grandeur; each line feels like a benediction whispered to those still bound by time.

Musically, the song exemplifies what made Wrecking Ball such a landmark recording. Lanois’s atmospheric arrangements dissolve genre constraints: gospel meets folk meets dreamlike ambient soundscapes. The spacious mix gives every note room to breathe, mirroring the song’s central metaphor of spiritual breath after bodily death. Harris’s harmonies—sometimes barely audible—create an almost ghostly choir behind herself, reinforcing the sense that she sings alongside unseen presences.

“All My Tears” endures as one of Harris’s most haunting performances because it confronts mortality without despair. It offers comfort not through denial but through surrender—a recognition that what we call loss may be the beginning of something infinite. In this way, the song is both eulogy and resurrection: a timeless reminder that within every ending lies the whisper of eternal grace.